When Russian President Vladimir Putin was not invited to participate in the 75th anniversary commemorations of D-Day held in France in 2019, he claimed it was “not a problem” because the Allied invasion of France on June 6, 1944, “was not a game changer.”

As the United States, Britain, Canada, France and other nations commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day this year, Putin again will not attend, this time because of the aggressive war he has waged in Ukraine. But it’s worth recalling the actual history of how Soviet media reported on the Normandy invasion, in which masses of Allied troops stormed the beaches and began the process of retaking Europe from the Nazis.

I study media and propaganda in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union in the 19th and 20th centuries. What Soviet citizens learned about D-Day was part of a carefully controlled media system. Soviet newspaper articles, political caricatures and radio reports recognized the significance of the opening of a second front in Europe, but downplayed its importance in the broader context of the war. They also reminded Soviet citizens that the invasion was long overdue.

Not front-page news

On the morning of June 7, 1944, the front page of the official Soviet Communist Party newspaper, called Pravda, meaning “truth” in Russian, only mentioned the D-Day invasion news in a small text box on the front page. Its main front-page articles were about improvements made to Soviet cities in the wake of Red Army victories and the ongoing military campaigns near Kishinev and Jassy – now known as Chișinău, Moldova, and Iași, Romania.

Page two contained telegrams thanking Soviet dictator Josef Stalin for his support of children of front-line soldiers. That page also included the fifth installment of an ongoing series entitled “The Road of Victory,” about Red Army victories.

On page three came D-Day, in an article with the headline “The Invasion of Europe Has Begun.” The correspondent, Maj. Gen. Mikhail Galaktionov, reported that the Allies had undertaken a massive operation designed to liberate Western Europe from the Nazis, and concluded that “the invasion of Europe is now taking place under unprecedented conditions in the history of warfare.”

The article was accompanied by a map of northern France complete with names that American readers would also soon learn: Cherbourg, Carentan, Arromanches and others. Pravda’s report accurately linked the Normandy landings to the ongoing liberation of Italy and stated that the main concentration of Germany’s army now found itself trying to defend Western Europe. Of course, as the newspaper report also correctly noted, the German army had been vastly depleted “after three years of war on the Soviet-German front.”

A photo of Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was on page four, alongside other coverage of the second front in Europe.

For Pravda, Allied forces attacking the defenses of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall on the French coast was just one among many moments in a war Soviet readers knew all too well, from years of fighting on their own soil.

For the English-reading audience

In the Moscow News, the Soviet government’s English-language paper, D-Day figured much more prominently, though it had to share the limelight. A front-page article included a photo of Eisenhower. “Allied Troops Land in Northern France, Take Invasion Beachheads” was the boldest headline in the June 7, 1944. But it was printed alongside an article on the major Red Army victory at Jassy, Romania.

Other front-page articles covered the successes of Soviet industry in winning the war, and how the capture of Rome by Allied forces represented “a major military and political victory.”

A page-three article in the English-language paper stated that “June 6, 1944, will go down in the history of World War II as a memorable date.” K. Hofman, the reporter, cited Winston Churchill’s announcement of the operation, described how news of the assault “flashed around the globe with the speed of lightning,” and particularly praised Eisenhower’s leadership.

D-Day as reported in the Moscow News meant that German armies now faced a “mortal threat of combined crushing blows by the Red Army from the East and the Allied armies from the West.”

A shift in tone

The Soviet media’s praise for both Churchill and Eisenhower might have taken some readers by surprise. The USSR’s leaders, journalists and propagandists had been lambasting the Allies for their failure to open a “second front” against the Nazis in Europe ever since the Allies promised to do so in 1942.

In an October 1942 issue of Pravda, the Soviet political caricaturist Boris Efimov published his cartoon “A Meeting of War Experts” about the “Discussion on the Second Front in Europe.” In it, “General Brave” and “General Determined” are trying to convince a group of older generals seated at a table: They are labeled as “General What-If-We-Lose,” “General Is-It-Worth-Risking,” “General Let-Us-Not-Rush-This,” “General Let-Us-Wait” and “General What-If-Something-Goes-Wrong.”

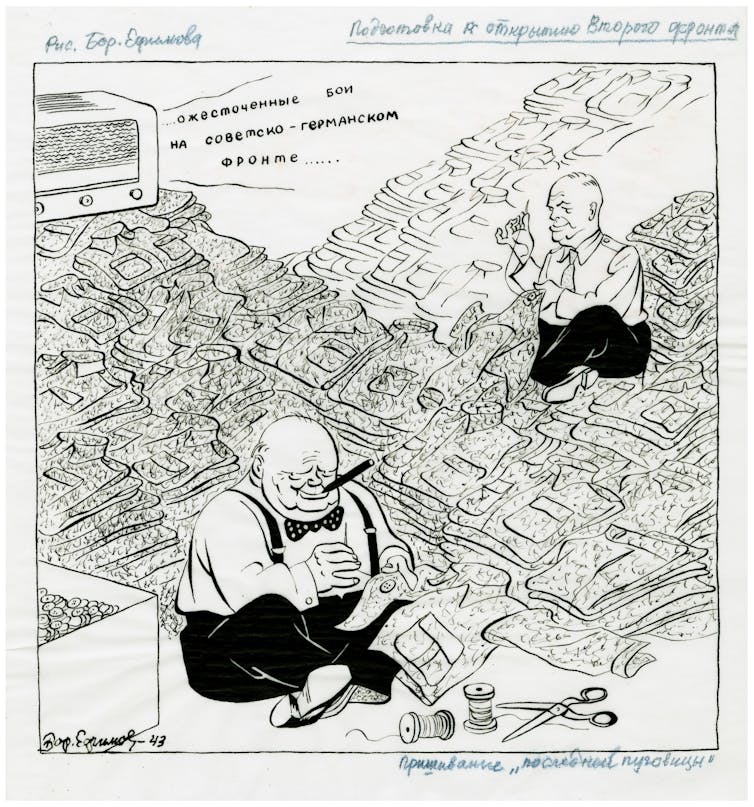

In other cartoons published in 1942 and 1943, Efimov specifically identified Churchill and Eisenhower as the architects of the delay. The caricaturist’s “Preparations to Open the Second Front,” for example, sees the British prime minister and American general sitting on a floor sewing buttons on uniforms while they listen to a radio broadcast about the “fierce battles on the Soviet-German front.” The implied message is that the British and Americans were deliberately stalling in order to allow the USSR to bear the brunt of Hitler’s violence. Rather than relieve the pressure, as Efimov and other press reports charged, Churchill and Eisenhower sat, smiled and listened to the radio.

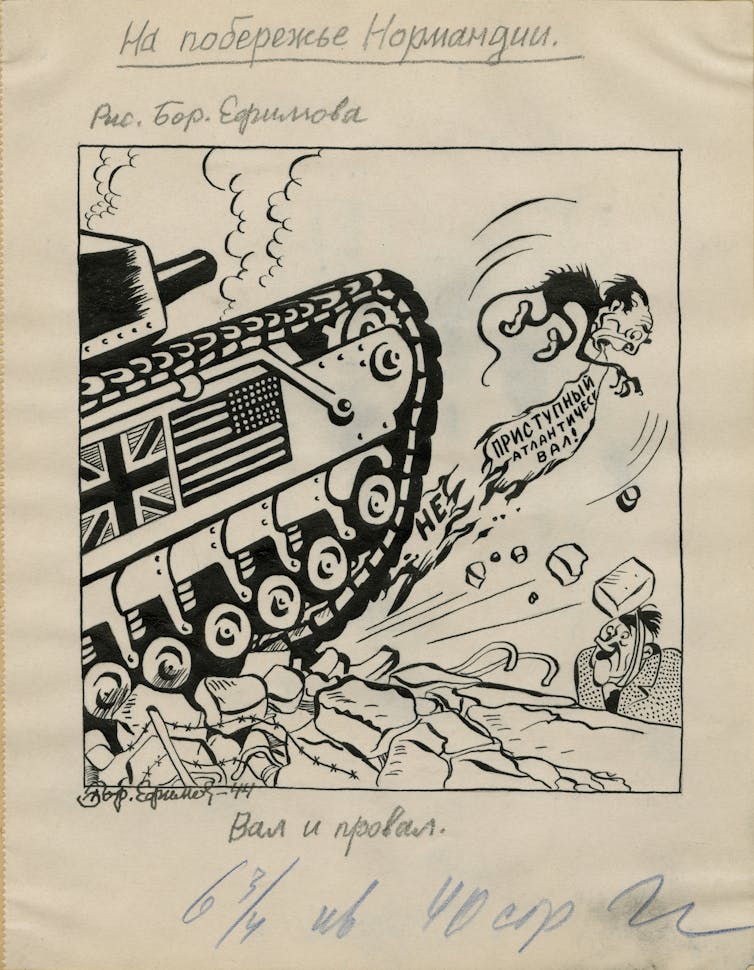

After June 6, and in keeping with other Soviet press reports, Efimov published two cartoons highlighting D-Day. “On the Beaches of Normandy” is dominated by a tank bearing the British and American flags. As it crushes the German fortifications beneath its wheels, the tank also sends a beastlike Joseph Goebbels scrambling away, his speech on “the unbreakable Atlantic Wall” torn apart while Hitler crouches glumly in a corner.

In another cartoon, “On Walls and Falls,” published on June 12, 1944, Efimov reminded Soviet readers of their nation’s contributions to the war effort. Goebbels, Gen. Erwin Rommel, Hitler and Hermann Goering stand atop a wall still emblazoned with a sign warning of the “Impregnable Atlantic Wall.” Behind his back, however, Hitler clutches a list of other “impregnable” fortresses, which had all been captured by the Red Army in 1943. D-Day was an important event, Efimov’s cartoon illustrates, but it suggests the most important destruction of the Nazi war machine had been accomplished by the Soviets.

Prelude to the Cold War

Memories of the delay in opening a second front would linger for a long time in the USSR, growing into Cold War grievances. After Churchill delivered the famous March 1946 speech in which he labeled Soviet influence an “iron curtain” across Europe, Efimov would mock him relentlessly as the same nefarious type who had sewn buttons while Soviet soldiers and citizens suffered. Soviet propaganda transformed Eisenhower, who was the U.S. president from 1953 to 1961, into a stereotypical warmonger.

As the decades passed, Soviet media outlets downplayed or ignored D-Day. Instead, they highlighted the sacrifices Soviet citizens made fighting the Germans, the “anti-Soviet” feelings that delayed the opening of the Second Front, the victories won at Stalingrad and other Soviet-centric perspectives. D-Day remained page three news at best, “not a game changer” then – or, for Putin – now.![]()

Stephen Norris, Professor of History; Director of the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies, Miami University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.