This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters

This story was reported in partnership with Open Campus.

Sign up for our free monthly newsletter Beyond High School to get the latest news about college and career paths for Colorado’s high school grads.

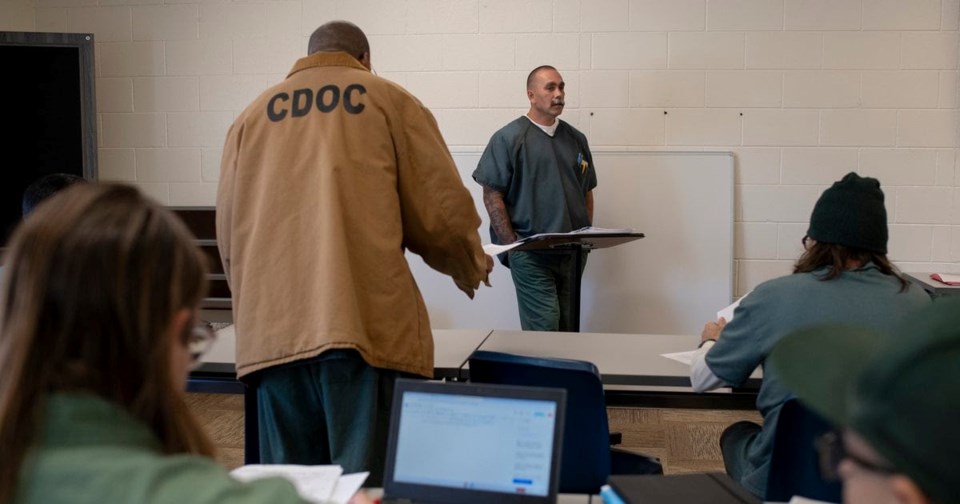

CAÑON CITY, COLORADO — On a late-November afternoon, at the head of a cramped classroom, David Carrillo stood at a small podium and quizzed 17 students on macroeconomic terminology.

For the two-hour class, Carrillo, the adjunct professor teaching for Adams State University, mostly kept his hands in his pockets as he lectured students in green uniforms, some bright and others faded with time. His lecture came rapid-fire, allowing just enough time for students to answer questions or let them ask a question of him. One of the lessons on that day: banking.

“Banks keep track of all of their transactions on their balance sheet, but they use a specific type of accounting tool to keep track of all this. What’s that accounting tool?” Carrillo asked his class.

Like his students at the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility, Carrillo, 49, also wears green. He holds a position that is extremely rare in prison: He’s an incarcerated professor teaching in a prison bachelor’s degree program.

A new initiative at Adams State — one of the first of its kind in the country — focuses on employing incarcerated people with graduate degrees as college professors, rather than bringing in instructors from the outside. The program offered through the Alamosa-based university gives incarcerated graduates experience and training while helping to alleviate the staff shortages that can hinder prison education programs.

Carrillo knows firsthand the power of education — he was never supposed to get out of prison. But in December, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis granted Carrillo clemency for his role in a 1993 murder. Carrillo will walk free later this month after 29 years thanks in large part to his work to educate himself and find a productive way to do his time.

Carrillo, whose new prison nickname is “Professor,” wants his students to have the same opportunities that will help them restart their lives.

“To be able to help these guys realize that they are capable of doing so much more — that’s a reward right there,” said Carrillo, who earned his MBA from Adams State in 2021.

An idea almost unheard of in prison

The Adams State program began with an unusual proposal from Leigh Burrows, associate director of prison programs for the Colorado Department of Corrections. In 2022, she approached the university and asked: Would they be willing to hire an incarcerated professor to teach in their business bachelor’s program at Colorado Territorial?

Adams State staff jumped at the opportunity, on the condition that the instructor be paid the same as adjunct professors teaching on its main Alamosa campus. The idea — hiring an incarcerated professor to teach incarcerated students and paying him outside wages — is almost unheard of in correctional settings.

“A lot of people thought we were insane,” Burrows said.

Most people in Colorado prisons only make 80 cents a day, so it would take them around 17 years to earn the $3,600 that Carrillo gets for a single class. Higher wages help incarcerated individuals build savings to help cover their basic needs when they are released. Poverty can often be a driver of decisions that land people back in prison.

A few other states are experimenting with hiring incarcerated faculty. In Maine, for instance, Colby College has hired an incarcerated instructor to teach an anthropology course on mass incarceration to outside undergraduates via Zoom. And officials from other state corrections departments have expressed interest in Colorado’s program, Burrows said.

Six colleges currently teach in Colorado’s prisons, including three public institutions that enroll a total of 311 students in degree programs. And college programs in prison are poised to grow over the next few years, especially since in July incarcerated students became eligible for Pell Grants – the federal financial aid for low-income students – for the first time in nearly 30 years.

But prison education programs face a number of challenges: Colleges sometimes struggle to recruit qualified faculty and correctional facilities are increasingly short-staffed. After several years of ongoing shortages, about 13% of Colorado’s correctional officer positions were vacant, according to a Colorado corrections department spokeswoman.

Burrows’ idea of utilizing the talent that exists behind bars helps mitigate those issues. Incarcerated faculty are already on site, eliminating the need for correctional staff to escort outside professors. It also creates opportunities that allow incarcerated graduates such as Carrillo to put their professional knowledge and skills into practice — and earn a living wage while doing so.

Incarcerated students benefit, too, by having professors that understand their backgrounds.

Clinton Hall, one of Carrillo’s students, said the opportunity to take a class from him is better than learning from other professors who have never been incarcerated. Hall and Carrillo live in the same pod, and it’s easy to find “Professor” when he needs help.

“Anytime I got a question or I need some clarification on my work, or I just want to kind of dig in a little bit more, I can walk over,” Hall said.

He also likes that Carrillo understands if students encounter challenges unique to being incarcerated. If there’s a lockdown, for example, Carrillo works with prison staff to try and reschedule the class or get the assignment out to students.

And, education inside is proven to reduce recidivism. As of 2019, around one-third of people getting out of Colorado prisons went back within three years.

In Carrillo’s case, the benefits of education also played a key role in getting out of prison. Polis said that Carrillo’s journey to educate himself and work as a professor contributed to the clemency decision.

“It is evident that you have put in tremendous work while incarcerated to change your mindset and pursue educational goals,” Polis wrote in a letter to Carrillo.

Carrillo’s experience also highlights the importance of professional opportunities for people inside, said Lauren Hughes, the director of Adams State’s prison education program.

“David cracked the barriers and we will continue working towards breaking them all down to get more people home through education and employment opportunities,” she said. “It’s a one-person-at-a-time, slow movement-building kind of work, and as we expand this to more individuals I know we will keep seeing this kind of result.”

Burrows said her goal is to hire two additional instructors by the end of 2024, beginning this summer with having an incarcerated woman with a law degree teach business law in the Adams State’s bachelor’s program at Denver Women’s Correctional Facility.

A second chance after solitary confinement

In 1994, at the age of 20, Carrillo received a life without parole sentence for his complicity in a murder. The year before, he was present when someone was killed. Colorado law at the time considered him just as guilty as the other teenager – his brother – who pulled the trigger.

“I’ve been in and out of the system since I was a kid,” he said. “I’m generational to this.”

Almost a decade later, in 2002, Carrillo found himself in a solitary confinement cell barely the size of a parking space. He had spent years involved in prison gangs. As he sat alone, he decided he needed a change that had to start with him.

“My worldview was very narrow for a very, very long time,” he said.

Although the 20-year-old Carrillo never would have imagined himself at the front of a classroom, the transition from student to professor wasn’t hard. He had already led several self-help programs, and received plenty of support, including classes from Red Rocks Community College to get his adult education certificate.

Adams State hopes to eventually employ more graduates of their own programs in the future, said Hughes, the prison education director. Currently, Hughes said around 100 people in prisons across the country are working towards their MBA through Adams State like Carrillo did.

The 36-credit print-based MBA correspondence program costs $350 per credit for a total of $12,600, plus textbooks. And, there is no state or federal funding to assist with a graduate degree, so students have to pay out of pocket.

Last fall, Adams State received a $150,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation that will be used to hire a program coordinator, develop a training curriculum for the incarcerated instructors, and create a new graduate program in the humanities.

Hughes, who is herself formerly incarcerated, said she was able to attend college for free while she was inside because of a privately funded prison education program in New Jersey. Many incarcerated people don’t have the resources or family support to fund their own education, and she’s hoping to do fundraising to be able to offer more support to their students.

The state also wants to help more incarcerated individuals earn high school equivalency diplomas so they can take college classes like the ones Carrillo teaches. But Colorado is facing an ongoing teacher shortage across its 19 state-run prisons.

As of December, there were 31 vacancies out of 148 teaching positions around the state, Burrows said. Some of those teachers retired, others have quit because they were conscripted to work custody positions when facilities were short on correctional officers, and facilities have faced ongoing recruitment challenges since the pandemic.

So Burrows is also working to build a pipeline to train peer teachers who could help people study for the high school equivalency exam on their own and then go on to college. As a result, “we’ve had a number of individuals get GEDs who would not have gotten them otherwise because of their sentence length,” she said. Traditionally, the more years a person has left to serve, the lower they are on the list to take GED classes.

Burrows said she recently put out an ad on the department’s television system announcing that they are going to be looking for individuals with everything from an associate to master’s degrees to assist with peer tutoring and teaching. It’s generated a lot of interest.

“Now I can’t go into a facility now without having someone come up to me and ask what they need to do,” she said.

When your students are your roommates

Initially, Burrows heard concerns within the corrections department that hiring Carrillo and allowing him to supervise other prisoners could create a power dynamic that allows for exploitation. But that hasn’t turned out to be a problem.

“Back at the cell house, my friends, they still joke with me as always,” Carrillo said. “They’ll still throw potshots.”

Carrilllo said he doesn’t mind that his students have access to him 24/7. In fact, there’s one student Carrillo couldn’t get away from even if he wanted to: his cellmate Sean Mueller.

The two have lived together for over 13 years. Even as Mueller struggled with his own education, he watched as Carrillo earned a paralegal certificate, then an associate degree, a bachelor’s and finally his master’s.

Mueller said a short-term mindset, pride, and greed got him into prison. Now, he’s thinking about the long-term in part thanks to the influence of Carrillo.

Carrillo’s class will help Mueller get one step closer to an associate degree and his release. Last year, Colorado legislators approved a law that deducts time off a sentence for prisoners who committed a nonviolent offense if they earn a college degree.

Mueller will be one of the first in the state to be able to take advantage of the new law after he earns his degree, he said.

Mueller will likely not be the last. Hall, Carrillo’s podmate, said Carrillo’s class is “gaining popularity and momentum.”

“We’ve got guys who are asking, ‘How do I get into this class?’,” Hall said.

Before Carrillo received the news that he’ll parole on Jan. 31, he said he’d like to keep his job teaching at the prison if he ever got out.

“I didn’t expect this,” he said. “Once I was leading guys into this place. Now, I’m doing my best to lead guys out.”

Chalkbeat Colorado partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage.

Jason Gonzales is a reporter covering higher education and the Colorado legislature. Contact Jason at [email protected].

Charlotte West is a reporter covering the future of postsecondary education in prison for Open Campus. Contact Charlotte at [email protected] and subscribe to her newsletter, College Inside.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.