This content was originally published by the Longmont Observer and is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

Those days are gone. The once bucolic countryside north of Denver is now bustling with development. Traffic on I-25 can be brutal and we have more than our share of road rage and missed appointments to show for it.

There is no slowdown in sight and the population in the I-25 corridor is predicted to double by 2040.

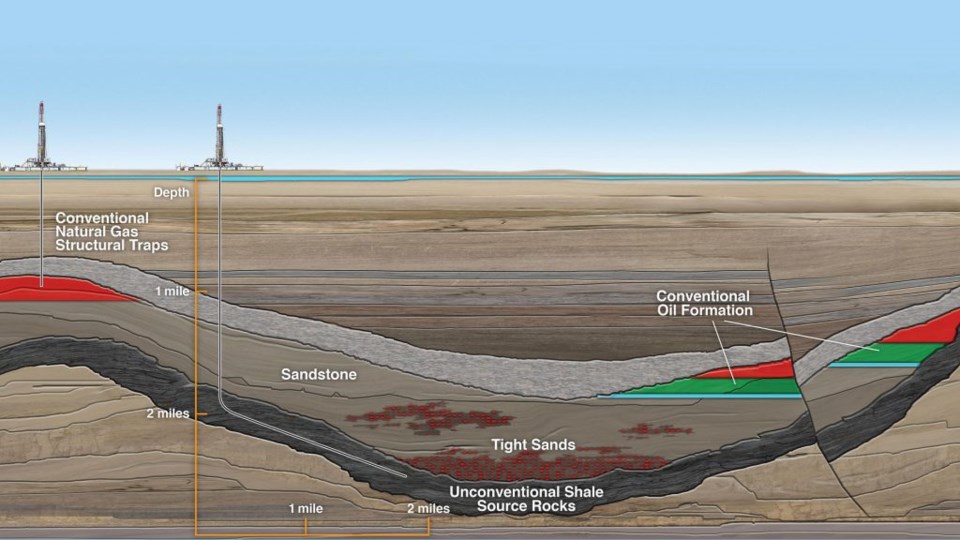

Twenty years ago Colorado’s oil and gas industry was booming on the eastern plains. Morgan County had wells reaching into underground pools rich enough to make it one of the top oil-producing counties in the country. Although there was abundant oil closer to the Front Range, it was locked securely in layers of shale 6,000 feet under rolling farmland and no one had the ability to extract it.

Today, much of the easy to reach oil is gone, leaving behind thousands of capped and abandoned wells. New drilling technology to extract what’s trapped in those rich shale layers allow operators to regularly drill over a mile down, then several miles horizontally to tap the remaining deposits of oil and gas.

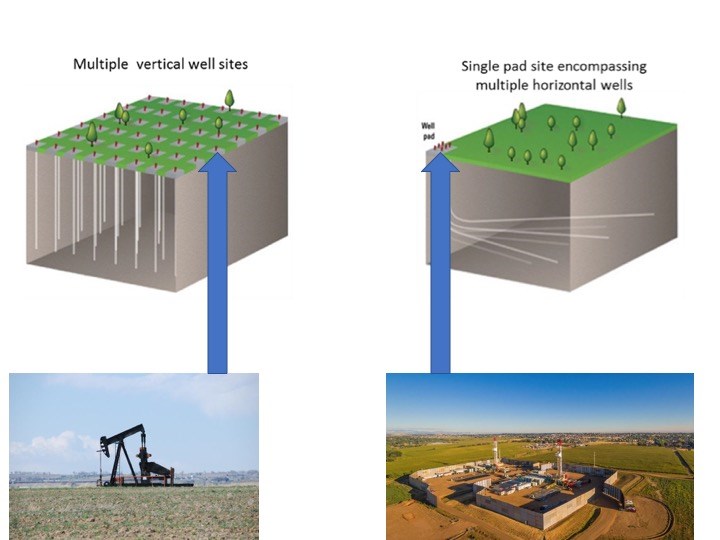

Where older technologies spaced wells out in a grid to get at vast pools under the earth, the new methods put 10, or 20, or 30 wells on a single “pad” creating a pattern of horizontal paths miles on a side deep under the ground.

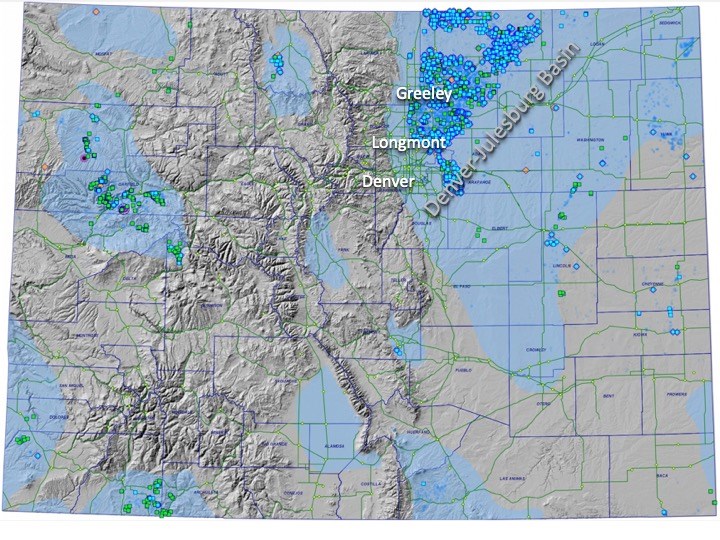

In places like North Dakota’s Bakken oil field or Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, there is little competition between land development and drilling for oil and gas. Not so for the Niobrara shales in the Denver-Julesburg Basin.

In places like North Dakota’s Bakken oil field or Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, there is little competition between land development and drilling for oil and gas. Not so for the Niobrara shales in the Denver-Julesburg Basin.

Today, horizontal drilling and fracking account for around 85% of all new wells in Colorado. Most of them are just east of the Front Range north of Denver. I-25 runs right through the richest deposits in Colorado and Greeley is pretty much smack dab in the middle.

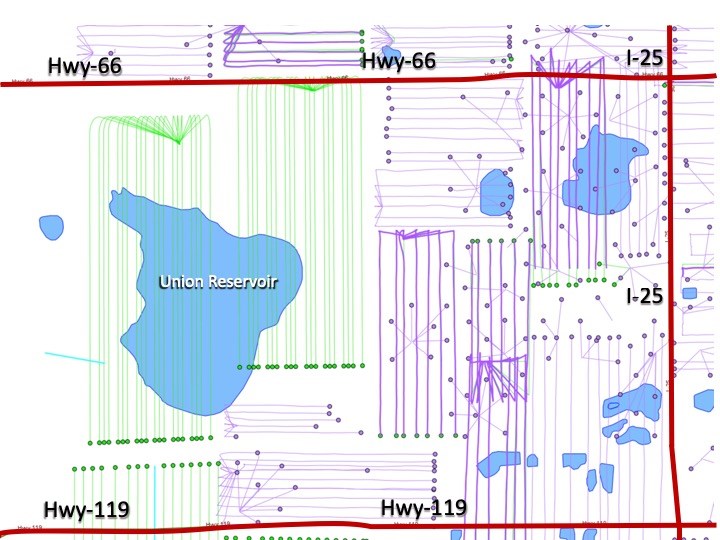

Horizontal drilling pads are serious industrial complexes with the ability to drill, case, frack, pump, and store large quantities of oil and natural gas. Much of the friction between homeowners and the oil and gas industry can be attributed to the industrial facilities located close to suburban neighborhoods. Noise, dust, and heavy truck traffic are common complaints. City citizens are voicing concerns over the health and environmental effects including the release of hydrocarbons into the atmosphere and spillage of toxic fluids that can contaminate aquifers, rivers, streams, and reservoirs.

Starting in 2012, the increased density of existing and proposed drilling sites in close proximity to Front Range cities spurred the passage of fracking bans and moratoriums in Longmont, Fort Collins, Lafayette, Boulder, and Broomfield. At the same time, the Colorado Oil and Gas Consortium was working on new rules to establish more stringent setback distances between new oil and gas development and occupied buildings.

In 2013 the new rules went into effect increasing setback distances to 500 feet for residential building units (single-family homes), and 1,000 feet for high occupancy building units (schools, hospitals). Citizen group efforts to further increase those setback distances began quickly after the adoption of the 2013 rules with a proposed ballot measure: Initiative #88. Initiative #88 proposed 2,000-foot setbacks from the nearest occupied structure but allowed a landowner to wave the setback requirements for any structure on their property.

Governor John Hickenlooper and Representative Jared Polis agreed to create a task force to review oil and gas activities to find an alternative to the ballot measure. Initiative #88 was withdrawn.

Hickenlooper appointed members to an Oil and Gas Task Force in September 2014 and by early 2015 the task force submitted nine non-binding recommendations, several have been adopted into state law.

Citizen groups were not satisfied with the task force results and Initiative #78 was filed in late 2015 proposing 2,500-foot setbacks between new oil and gas development and occupied structures. The initiative added “Areas of Special Concern” including lakes, reservoirs, and rivers on federal and non-federal lands to the setback mandate. Initiative #78 failed to achieve the number of valid signatures necessary to be placed on the 2016 ballot.

Longmont and Fort Collins bans were struck down by the Colorado Supreme Court in 2016 and Broomfield withdrew its ban in the face of the Supreme Court decision. Lafayette’s 6-month moratorium expired but in May of this year, but Boulder extended the city’s moratorium for an additional two years to May 2020 in violation of state law, according to Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman.

The Colorado Supreme Court decision is based on a legal hierarchy called preemption that allows state statues to overrule, or preempt city statutes. “Accordingly, the court holds that Longmont’s fracking ban is preempted by state law and, therefore, is invalid and unenforceable,” Justice Richard Gabriel wrote in the 2016 decision.

Initiative #97 was filed with the Colorado Secretary of State in January 2018 and met the August 2018 deadline for signatures necessary to be placed on the November 2018 ballot as Proposition 112. It is similar to Initiative #78 in that it seeks to increase setback distances for new oil and gas development to 2,500 feet from occupied buildings and vulnerable areas. Initiative #97 would take effect upon declaration of the governor and would apply to oil and gas development permitted on or after the effective date.

Opponents of Initiative #97 label it as effectively an outright ban on oil and gas activity in Colorado.

Statewide bans are rare in the US. Vermont banned fracking in 2012. It’s arguable whether or not it’s really a ban as there are no known frackable reserves in the Green Mountain State. New York banned the practice in 2014 and Maryland enacted a two-year moratorium in 2015 followed by a bill banning the practice in April 2017.

In Europe, oil and gas production close to densely populated areas has also been a controversial issue and entire countries – France, Germany, Bulgaria, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland – have banned onshore hydraulic fracturing for health and environmental concerns.

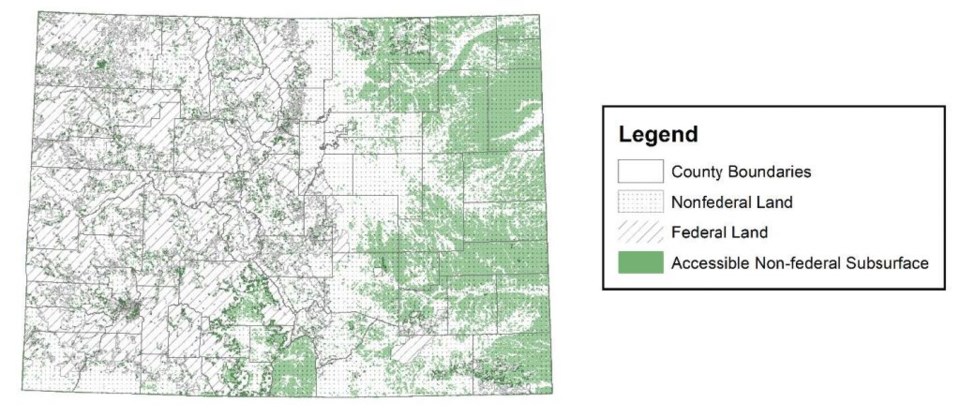

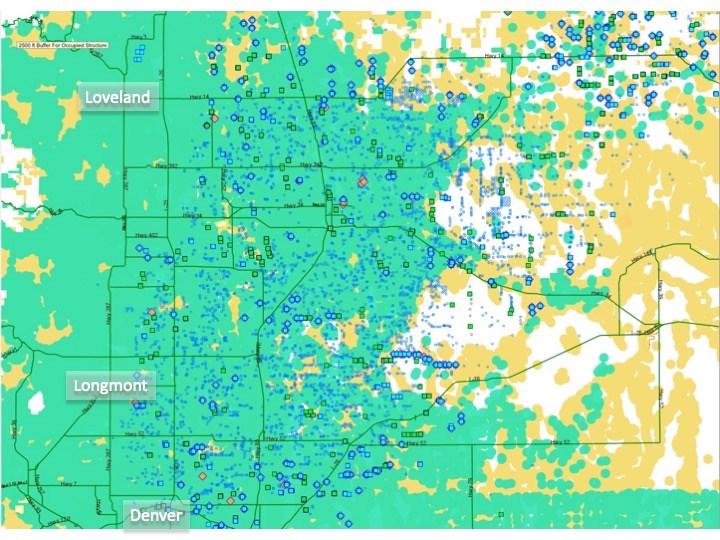

At the request of its commissioners, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Consortium developed a map depicting 2,500-foot setbacks per Initiative #97 language to help assess the impact on permitting for oil and gas development. Those maps show the expected restrictions and additional limitations the proposed setbacks from vulnerable areas are anticipated to have. According to the maps, the combined effect eliminates 78% of the surface area in Weld County for oil and gas development. Weld is the dominant oil-producing county in Colorado.

New drilling and extraction technologies change the game, however, and oil and gas development no longer has to take place directly above valuable deposits. Horizontal wells currently extend several miles, and that has the potential to change the question from “what surface area cannot be used?” to “how much of the subsurface resource would be inaccessible?” At the Colorado School of Mines, Dr. Peter Maniloff used COGCC data to get a rough estimate for the resource denied by Initiative #97 setbacks using a 1-mile horizontal drilling capability assumption. In his paper, Dr. Maniloff says, “I find that 42% of the non-federal subsurface would be accessible, or nearly three times the available surface area [shown in the COGCC maps].”

Dr. Maniloff’s paper has come under fire, most notably from fellow Colorado School of Mines professor Dr. Will Fleckenstein. Fleckenstein contends Maniloff didn’t take into account things like the surface area needed for well pads, tanks, flow lines, and other infrastructure. He points out that a vast majority of the 42 percent of non-federal land referenced in Maniloff’s paper is located outside the concentration of rich deposits in the Denver-Julesburg Basin.

The COGCC says their maps were never meant as a complete analysis of the effects of changing setbacks and Maniloff’s approach asks the right question: “how much of the state’s resource will be made unavailable by changing the rules?” It just isn’t comprehensive enough.

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)