Editor’s note: This story was originally published by CPR News and was shared via AP StoryShare.

Emotional intelligence and ethical decision-making training will be offered to law enforcement officers across the state within the year — and officials hope it will give them more tools to deal with the increasing stresses of the job.

This new training — being developed now by the state attorney general’s office — seeks to go way beyond the “implicit bias” training academies are already doing.

It attempts to teach officers how to carefully listen to victims and suspects, and how to be more tuned in to their own emotional state at any given moment. It also seeks to train officers on how to read their work partner’s moods and to suggest they take a breather if they’re not in the right frame of mind.

“We have not emphasized emotional intelligence as a critical competency,” said state Attorney General Phil Weiser, whose office is working on the curriculum with the Peace Officer Standards and Training Board, which certifies law enforcement officers statewide. “The goal is not to only train them in technical skills, but also how to listen.”

The point, Weiser said, is that interacting with people is as important a skill for an officer as knowing how to use a firearm.

The new training comes at a time when law enforcement officers face increasing scrutiny on the job.

In the last year, Colorado prosecutors filed seven charges against five officers for failing to intervene on the job when one of their fellow officers was committing misconduct. It’s also easier to sue law enforcement officers directly in Colorado now thanks to the passage of Senate Bill 217 in 2020.

These changes are often cited by law enforcement as reasons why it’s such a challenge to find qualified police officers to fill hundreds of openings at agencies across the state. A recent survey found that three-quarters of all agencies had openings for officers, with law enforcement leaders reporting it’s extremely difficult to find people to staff patrol and jail shifts.

Weiser says this is why enhancing and improving the preparation officers get is so important right now.

“Those who serve as police officers are taking a very dangerous and important responsibility,” Weiser said. “And we need to train them properly.”

From bad interactions to brutality

The cost of officers not controlling their emotions on the job can be significant — both for the officers, and the people they serve.

Two Aurora officers recently lost their jobs after one of them violently arrested a man who had an outstanding warrant. The officer who beat the man is charged with felony assault, the other faces a “failure to intervene” misdemeanor for not stopping her partner.

Beyond the headline-grabbing incidents, though, are more subtle interactions between officers and the public that, when handled carefully, can engender more trust in law enforcement.

Weiser brings up an example of a victim who has just had a car stolen.

“If you think about that victim only as someone who gives you facts to help you solve the crime, you’re missing the emotional part of the equation, which is: you have a person in front of you, ‘how are you doing? Do you know how you’re getting home? Do you need someone to talk to?’” Weiser said. “An officer who has that awareness, that emotional intelligence, will be more effective.”

Denver Police Commander Kathy Bancroft tells a story of two of her officers answering a call about a potential juvenile suicide in northeast Denver. When the officers arrived at the grandmother’s house, they were brusque with the older woman when talking to her.

The grandmother later complained to Bancroft about it.

“She was taken back by the sternness of the officers. We can seem like we’re all business sometimes. We may be worried about the next call … or we might be coming in on a child who killed themselves so we’re preparing for that,” Bancroft said. “We can do better though.”

Bancroft said once the pandemic has subsided enough to make it safe to meet, she plans to get the officers together with the grandmother to talk about what happened.

“We can learn from this,” Bancroft said.

‘A difficult and complex field’

At the Community College of Aurora’s Police Academy, instructors have already bulked up emotional intelligence training in the curriculum for would-be future officers.

“We’re moving them into seeing the world through the lens of someone else,” said Police Academy Director Michael Carter. “Every time you go into a home, say it’s a domestic call: look at the pictures, look at what’s on the floor … Think about the family.”

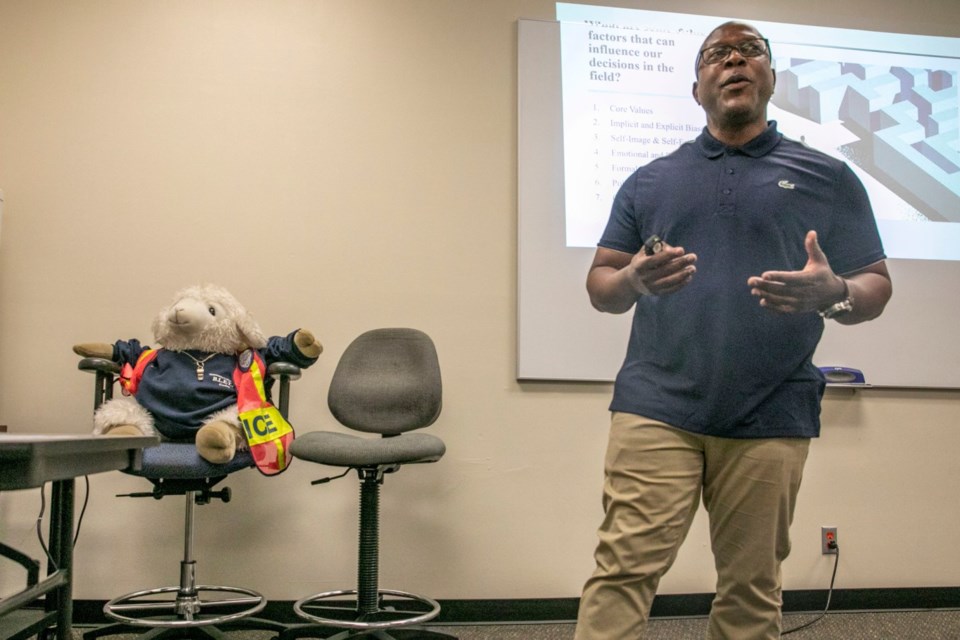

Kevin Watts is a federal law enforcement officer by day, and at night trains cadets on implicit bias and emotional intelligence as an adjunct professor in Aurora.

In the last two years, he and Carter have worked to make emotional intelligence, as a concept, more concrete. They talk to cadets about who they are, where they come from, about law enforcement culture, current events and how it all fits together to influence officers as they do their work.

“We saw that when we’re looking at the decisions made in the field, there are so many factors that can influence it. If we ignore one ... we’re doing ourselves an injustice,” Watts said, pointing to how officers can be affected by current events and movements like Black Lives Matter or Stop the Steal. “And whether we want to admit it or not, these are going to influence you … It’s OK to let them influence you but they can’t let them drive you.”

Watts, who is Black, also talks to the cadets about their self-esteem and how to mitigate negative moods in the field. He talks about how use of force affects communities of color and he has asked cadets to watch videos of interactions between people and law enforcement officers to tease out what went right and what went wrong.

Watts said he’s seen a transition in the last few years.

“Things have changed,” he said. “I think there is more of an acknowledgment now that this is a difficult and complex field. There is no simple, one-dimensional approach to doing things … There is a lot of breadth to it. We need to treat it as such.”

The community college’s program is ahead of the statewide training being developed within the Peace Officer Standards and Training staff — but officials hope to have offerings for new and existing officers within a year.

“One of the challenges we have is modernizing how we think about policing. The curriculum we have today is shaped from a generation or two ago,” Weiser said. “We need to ask what are the competencies that successful peace officers need? How do they engage in very difficult situations with people with mental illness? And act ethically, and act in a careful manner?”

The attorney general does acknowledge how hard it can be for officers — particularly those right out of an academy — to prioritize emotional intelligence and de-escalation as they do an increasingly dangerous job.

Assaults against officers are up and illegal gun possession and gun crimes are at a high point in the state. In Denver, for example, officers have seen a 64 percent increase in gun-related crimes against people and seized 25 percent more firearms compared with a three-year average — that is just in 2021.

Weiser said these numbers show how important additional training is for officers right now.

“It’s important to recognize that those who serve as police officers are taking on an important and dangerous responsibility,” he said.

Training for danger

To help officers prepare for that reality, many departments employ one of Todd Brown’s computer programs.

Brown is an owner of TI Training in Golden, which provides interactive training simulators for departments and cadet academies. His clients range from the New York Police Department to Winter Park’s Police Department.

On a recent day earlier this summer, officers, armed with tasers and Glocks loaded with blanks, were going through various video scenarios, including hostage situations and officer shootings.

“Everything is a potential threat,” Brown said in a darkened room with a life-size simulation of a warehouse break-in, where a virtual shooter hid behind some barrels. “We just need to be aware of it.”

But Brown said that even in these terrifying training sessions, which often involve officers being shot at, he tries to introduce nuance — and the need to think through situations thoroughly as well as quickly.

“We’re very cognizant of the fact that if all we give them is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” Brown said. “What I want people to understand is de-escalation is a process, it’s not a result … We don’t want to train them that everyone is going to shoot them because that’s not the reality.”

At the police academies — particularly for brand new officers — leaders are attempting to get the cadets ready for everything.

Jay O’Bara is more than halfway through his officer training at the Community College of Aurora.

He’s followed the ongoing debate around the country about policing and said when he puts on a uniform for the first time, he wants to put his training in ethics and emotional intelligence to immediate use and take a proactive approach.

“We need good officers now more than we did in the last 50 years,” O’Bara said. “I’m excited to see what I can choose to do to help my community, rather than just sitting with my hands in my pocket waiting to get a call.”

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)