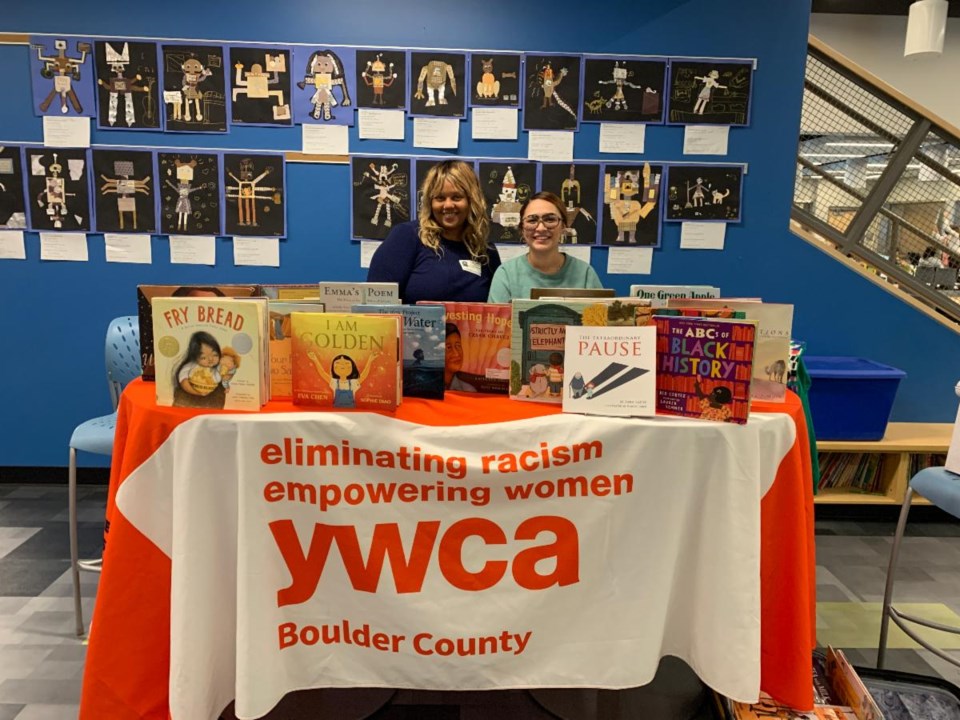

The Reading to End Racism program through the YWCA is celebrating a decade of sparking hard conversations among elementary and middle school students in an effort to eliminate racism, bullying and discrimination.

Reading to End Racism began in 1998 as a grassroots effort by retired local teachers. “They have seen racism and discrimination in their classrooms and wanted to create a safer, more supportive educational environment for local students,” according to the YWCA’s website.

In 2006, a partnership between the Reading to End Racism staff and the YWCA grew into a relationship that allowed the program to merge into the YWCA’s services in 2013.

For 10 years, trained volunteers have chosen books to read to elementary and middle school students. Although the practice sounds simple, these volunteers do more than read, they provide a space for children to have difficult conversations without feeling shame.

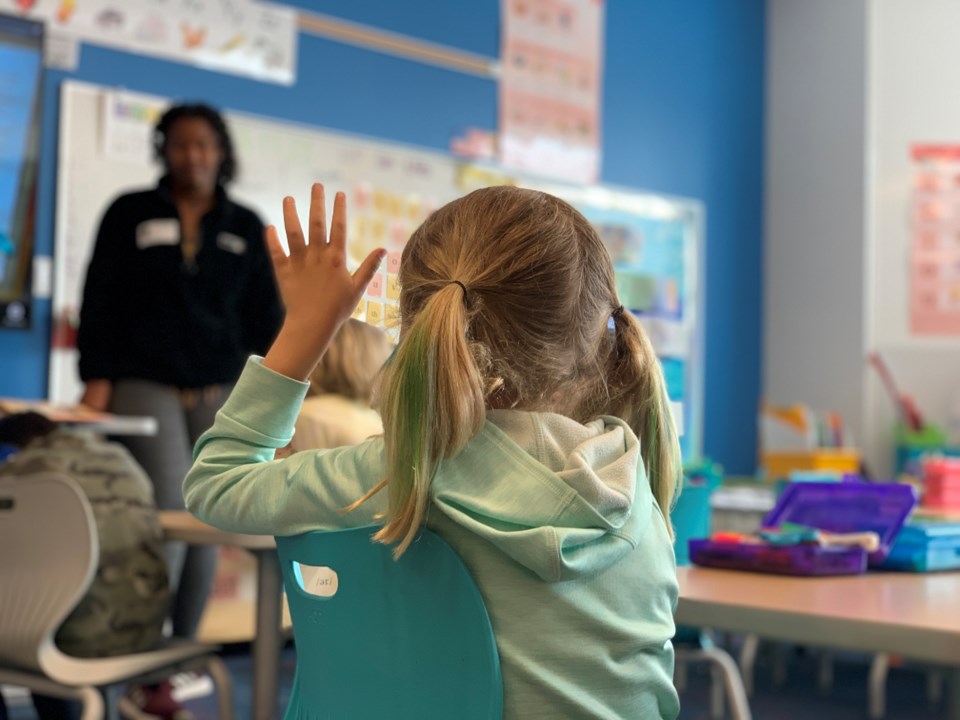

“It is a great opportunity for those students to have the opportunity to raise their voices and speak out in how they feel. And just to see someone come into the classroom to talk about those issues while they are in there, they feel like ‘This is my chance. This is my chance. My opportunity,’” said Shiquita Yarbrough, director of Community Engagement and Equity.

The program uses literature to evoke empathy in children to understand how the characters feel and how they might feel in a similar situation, according to Debbie Pope, executive director of YWCA.

The program has grown over the years, reaching an average of 17 schools each year in the Boulder and Boulder Valley School District. Recently the YWCA added a training session for parents so they could continue the conversation beyond the classroom and to learn how to talk to their children about racism, Pope said.

“There is an impact not just with the students, but it also transitions into an entire school … When those students learn how to be kind to one another and when we go in and teach them … and tell them why we are doing this. Why is this important to us? … For us to come in and speak as an external voice is much easier for a teacher,” Yarbrough said.

For Yarbrough — who not only organizes the program but also leads some of the conversations — the program allows young people to learn that they too have the power to make a change, even if it is small.

During a visit to a classroom, Yarbrough recounted a story of a second grader who was from India. He shared that he felt sad because teachers and his peers would often call him by the name of another student from India. This boy shared that although the two came from the same country, they didn’t speak the same language and were different in other ways too.

Yarbrough was able to lead the conversation to encourage students to brainstorm some ways they could address the problem. Together the group decided they would all make a bigger effort to call the boy by his name and to get other people’s names right too.

Both Pope and Yarbrough hope to continue to grow the program by expanding into more schools and gaining more volunteers. Currently, the program has 40 volunteers with around half of them consistently volunteering, reaching an average of 6,000 students a year. Yarbrough hopes to double the number of volunteers in order to reach even more students.

“We are really committed to doing this work in our community … We would love to be in every school, to have the opportunity to give us a try to go into every school … Once we go into these schools they say it is nothing like what we thought it was going to be. It is just holding those conversations and empowering the kids to lift their voices,” Yarbrough said.