Editor's note: This story was originally published by The Conversation in 2018. The Leader is republishing it in recognition of Pearl Harbor Day. Read the original here.

December 7, 1941. A date which will live in infamy. The United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan. The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific.

Thus began President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s speech declaring war against Japan. On the anniversary of Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, we do well to revisit these words, for they claim “casus belli:" provocation where war is a justified response.

Churchill had begged Roosevelt to enter the war against the Axis (Japan, Germany, Italy) for months, but without casus belli, the American President refused. The U.S. had a tradition of “non-interventionism” in European affairs, and its Congress had passed Neutrality Acts in the 1930s to prevent U.S. entanglement in the power politics of the old world that might lead to war. The attack on Pearl Harbor marked a violent end to this era, and the beginning of America’s rise to the centre of world power.

Narrative of redemption

Psychologist Dan McAdams writes that the narrative of redemption — a story turning from bad to good - is fundamental to the American national identity and character. Roosevelt cast his declaration of war just so: after recounting Japan’s military deeds, he says:

"No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory."

In the case of Pearl Harbor, history vindicated Roosevelt’s claim. There is consensus that America’s entry into the war was justified, in the United Nations and in American public opinion. Consensus is crucial to the force and magnitude of collective remembering. More than this, the consequences of American entry into the theatre of war warrants a redemption narrative casting the USA as a heroic nation in the making of modernity.

The Axis was responsible for the deaths of more than 20 million civilians worldwide (about half in Asia, half in Europe). American entry into the conflict coupled with Russians’ heroic defence of their motherland turned the tide against that brutality.

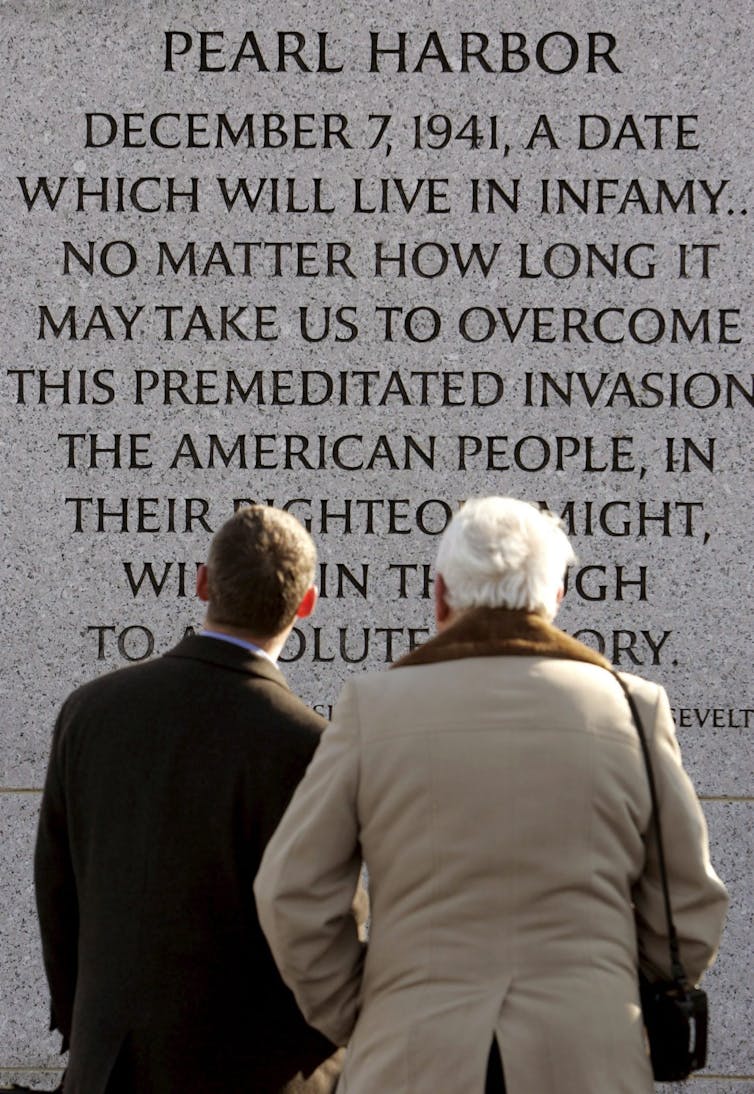

Visitors at the National World War II Memorial. EPA/Matthew Cavanaugh, CC BY-ND

Visitors at the National World War II Memorial. EPA/Matthew Cavanaugh, CC BY-NDTruth and facts

Narrative configures facts as “food for thought” in the greater meaning underlying its surface words. Because Stalin was a brutal dictator, and because Western democracies were going to enter into a half century of Cold War with the Communists over whose system would dominate, Russian heroism in WWII is less celebrated in the world’s collective remembering than American.

Churchill once quipped:

"History shall be kind to me, for I intend to write it."

Winners write widely accepted history as part of their story of why they have the right to rule. Losers’ versions of history are frequently forgotten, along with the facts that supported them.

Misquoting Alexis de Toqueville in 1983, President Ronald Reagan said:

"America is good. If America ever ceases to be good, America will cease to be great."

Reagan invented this quote to argue that the “shrewdest of all observers of America” attributed its greatness to church-going. He contrasted this with the godlessness of their great rival, the Soviet Union:

"While they preach the supremacy of the State, declare its omnipotence over individual man, and predict its eventual domination of all peoples on the earth, they are the focus of evil in the modern world."

History as soft power

Reagan understood that victory in WWII provided both the U.S. and the Soviet Union with soft and hard power. Even he practised military buildup, he negotiated for arms control, but ultimately undermined the soft power of the Soviets with speeches like this.

It was soft, not hard power that brought about the collapse of the Soviet Union. This required Soviet leader Gorbachev to buy into the story of glasnost (openness), which was most assuredly keyed to major themes in Western, not Soviet narratives (or its constitution).

The power of narrative is extraordinary, and not as well understood as hard power (e.g. armies). Stories about people like Hitler, the most evil man in the history of the world according to young people today, have the power to cast people and peoples as heroes and villains. These augment or undermine hard power.

The burden of history for the Axis nations Germany and Japan, cast as the villains of WWII, crippled their ability to assert global political power through the latter half of the 20th century, even though they were among the most powerful economies in the world.

The formation of the European Union was assisted by two complementary forces in terms of soft power: Germans needing a positive (superordinate) identity after the war, and French identity becoming more Europeanised as a way to bolster French power. While the signing of treaties forming the European Economic Community and then the European Union may have been decisive, historians assisted by developing more consensual accounts of the past that allowed new identities to emerge, ending more than a century of competition and revenge-based warfare between these two states.

By contrast, Japan’s inability to come to a consensus about the meaning of WWII with its neighbours has rendered Asia incapable of gaining the level of agreement necessary for an “Asian Union”.

The relevance of these collective memories may be fading as a focus of world attention with the rise of China. China’s rise is not a direct consequence of WWII, but the work of two to three generations following in its wake. History is a moving feast of lessons and identity positions that thrives as communicative or “living memory” of generations alive communicating to one another the stories of their lives.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor, and the heroism of the United States in response provided America with an unparalleled position of soft and hard power following WWII: a narrative of redemption. The near dismemberment of China and its suffering at the hands of Japan provided China with a different identity position and different lesson. As WWII fades from living memory, and new crises emerge to challenge our world, what new lessons and identity positions will the new century carve out?![]()

James H. Liu is a professor of psychology at Massey University

The Conversation is part of a nonprofit network of newsrooms that taps into academia to write about issues of national concern. The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors. Learn more about The Conversation at https://theconversation.com/us/who-we-are.