Editor’s note: This story was originally published by The Colorado Sun and was shared via AP StoryShare.

***

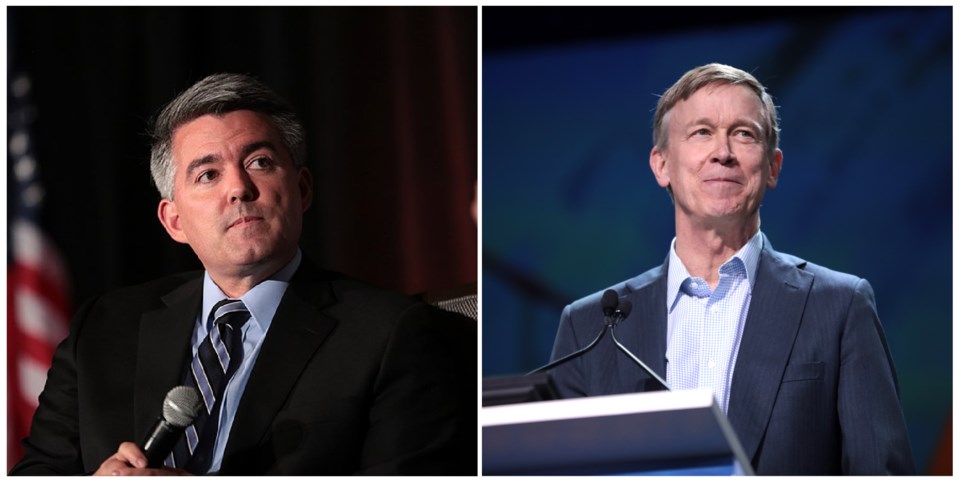

A television ad for Cory Gardner last month featured the former deputy director for Colorado State Parks saying the U.S. senator is “one of the few Republicans who fights for green energy.” The spot was titled “Both Parties.”

But Gardner strikes a far more partisan tone in his campaign emails. In one, he contrasts his environmental legislation with the “far-left’s socialist pipe dreams of a disastrous single-payer health care system.”

This difference in tone between Gardner’s emails and TV commercials is the norm, as is it in the campaign communications of former Gov. John Hickenlooper, his Democratic challenger.

The Colorado News Collaborative analyzed 684 emails sent between Aug. 22, 2019, and July 16 from Gardner’s and Hickenlooper’s Senate campaigns — 309 from Gardner and 375 from Hickenlooper. The analysis shows Gardner frequently using words such as “radical,” “socialist” and “far-left” in emails even as he casts himself as a bipartisan senator in television ads. It also shows Hickenlooper making frequent partisan references to President Donald Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

The pointed language in the emails frequently comes with solicitations for money — something the candidates never do in television ads, which are made for a more general audience — with Gardner frequently promising supporters that their donations will be matched, sometimes by a group of “generous conservative donors,” a strategy that campaign finance experts question because of federal contribution limits.

The Colorado News Collaborative’s findings reflect the audiences that campaign emails tend to reach, said Taewoo Kang, an assistant professor of political communications at Siena College who researches how politicians advertise themselves across different forms of media.

“Campaign emails are a set of communication tools that can be used for communicating with supporters,” Kang said.

Persuasion and mobilization

Email lists typically are made up of addresses offered by supporters responding to social media pitches or campaign websites, and sometimes are supplemented by purchasing lists of likely supporters from other campaigns.

Because they see email recipients as allies, campaigns use the more personal communications as tools to activate the faithful, Kang said.

“What you want to do is not to persuade (the audience) to vote for you, but to mobilize them and increase donations,” Kang said.

Email is a major source of funding for campaigns, said Jennifer Stromer-Galley, a professor at the School of Information Studies at Syracuse University who wrote “Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age,” a book on digital political campaign strategies.

In 2014, Senate campaigns requested donations in two-thirds of their emails, compared to none of their television ads, Kang’s research found.

Emails also regularly contain more partisan tones than television ads do. Kang recalled, for instance, the 2014 election campaign of Mark Pryor, a Democrat running for Senate in conservative Arkansas against the state’s current senator, Republican Tom Cotton. Pryor appeared in one TV ad where he held a Bible, calling it his “North Star,” and another where he highlighted his desire for a smaller government and his opposition to regulations from the Environmental Protection Agency.

But Pryor’s emails, Kang said, contained language much more typical of a partisan Democrat.

“You see this clear differentiation of campaign rhetoric or strategies by the same candidate within the same election cycle, because they know that they are clearly speaking to different audiences,” Kang said.

Partisan fighting

Kang noted that the kind of extreme contrast Pryor displayed in his campaign’s email and television rhetoric is not the norm. Some candidates are as partisan in their television ads as they are in their emails.

Gardner’s campaign — and, to a lesser extent, Hickenlooper’s — have geared their campaign messaging for individual audiences.

In 30-second ads posted on Gardner’s YouTube channel, for example, Gardner consistently touts his bipartisan track record. And in three TV ads, Gardner references the passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, a bipartisan conservation bill that Gardner sponsored and that passed the Senate by a 73-25 margin, with only Republicans voting against it. In another ad, Gardner shows Democratic Gov. Jared Polis praising his response to the coronavirus pandemic.

But Gardner’s campaign emails consistently use conservative messaging. Gardner used the word “radical” in over half of the 309 emails he sent, used the word “socialist” in over a quarter of the emails and used the phrase “far-left” in over a third of his emails.

“With my opponents pushing the radical socialist agenda that has taken the entire Democratic party by storm, I’m genuinely concerned about our future plans and our current successes being undone by their radical policy proposals,” one email reads.

In that same email, Gardner painted Hickenlooper as a “Schumer crony” – a reference to Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, a Democrat from New York. Gardner mentioned Schumer in 36% of 309 emails the Colorado News Collaborative analyzed, and “Chuck Schumer” in 19% of the messages, compared to Hickenlooper, who referred to Schumer in just one of his 375 emails.

Gardner’s campaign didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Tyler Sandberg, a GOP consultant and a former campaign manager for former U.S. Rep. Mike Coffman, an Aurora Republican, said that this kind of partisan messaging is standard in campaign emails on the left and the right.

“I don’t ever think that fundraising emails have that much distinction across candidates and races because they’re all operating backwards from the same kind of donor pool of small-dollar or online donors,” Sandberg said. “So I don’t generally read them. And I’ve written them for a living.”

Similarly, Hickenlooper has linked Gardner to McConnell, referencing the Senate majority leader’s full name in 47% of his emails. Gardner only referred to McConnell in 2% of his emails.

And Hickenlooper brought up Trump repeatedly, a favorite tactic among Democratic candidates, Stromer-Galley said.

“The Democratic candidates running at the Senate, House, maybe even the governor’s level … are going to try to pin their Republican challengers to Trump because Trump’s approval ratings are so low right now,” Stromer-Galley said.

To that end, Hickenlooper mentioned Trump in over one-quarter of his emails, while Gardner mentioned the president in just two of his. During the impeachment process, Hickenlooper regularly brought up the proceedings.

In January and February, he used the words “trial,” “impeachment,” “acquit,” “witness,” or “impeach” in over two-fifths of his emails.

But Hickenlooper also brought up Trump and McConnell in television ads. In one of his ads, he claims that Gardner is playing “Washington games” alongside Republican leaders.

“I don’t think Cory Gardner understands that the games he’s playing with Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell are hurting the people of Colorado,” Hickenlooper says in the ad.

In another TV ad, Hickenlooper brought up his record supporting abortion rights, showing him receiving praise from MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow.

The language Hickenlooper’s campaign has used in its emails is designed to appeal to the former governor’s grassroots donors, said Michael Sparks, the founder of the digital campaign strategy firm Ascend Digital Strategies and a former digital director for Polis’ gubernatorial campaign.

“Email programs are used in every campaign, from the local to the federal level, and for the most part, you are using those lists to target not undecided (voters) but to rally your base,” Sparks said.

But Sparks said that while Hickenlooper is targeting his emails toward an audience that already supports him, the candidate’s messaging is fairly consistent in his television ads.

“His emails honestly are in line with the overall message he’s advocating for to the wider Colorado audience,” Sparks said.

Money, money, money

Neither candidate is shy about emails seeking donations. Gardner suggested specific dollar amounts in 70% of his emails, while Hickenlooper used them in 62% of his.

When they referenced money, both candidates used partisan triggers, with Hickenlooper warning of “corporate PACs” trying to outspend his campaign and Gardner asking for “patriots like you” to donate.

Sandberg said that campaigns rely on these doom-and-gloom messages because they suggest to voters that there’s an urgent need to donate.

“In fundraising, it’s very much ‘the sky is falling, give now, save the world,’” Sandberg said.

Hickenlooper frequently warns his supporters that he is up against a powerful Republican machine, while encouraging them that they can “flip this Senate seat blue.”

Hickenlooper has used the phrase “special interest” in 18% of his emails and the word “billionaire” in 11% of his messages as he warns his supporters about the moneyed interests his campaign says are trying to keep Gardner in the Senate. (Hickenlooper’s net worth is at least $7.8 million and his campaign has received money from at least eight billionaires.)

This, too, a common theme among Democratic candidate emails, Kang said.

“You basically want to talk about these political actors and symbolic figures just to justify why it is important for you to make the donations,” Kang said. “But you do not see that appear in campaign advertisements.”

Hickenlooper at the same time has encouraged his email recipients that Democrats have a good chance of winning Colorado’s U.S. Senate seat, describing Gardner as a “vulnerable Republican Senator” in 8% of his emails.

Matching campaigns

Gardner has also extensively relied on promises to match candidates’ donations, a campaign email strategy that does not appear in any of Hickenlooper’s emails.

Gardner used the phrase “5x match” and other variants in close to two-fifths of the emails analyzed.

Sheila Krumholz, the executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan group that tracks money in politics, said such matching schemes are common in the nonprofit space. Super PACs, she added, can also deploy the strategy.

The idea, she said, is to urge supporters to donate to an organization quickly.

“It incentivizes donors to think that their donations will go farther if they act fast,” Krumholz said. “So there’s always a connection to a message of urgency.”

But while campaigns on both sides of the aisle, including McConnell and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, have promised matching contributions in emails, it’s unclear how such a strategy could work in the context of campaign finance laws.

Unlike super PACs and nonprofits, federal law limits the amount a donor may give to a candidate to $5,600 in an election cycle. That limit could make it difficult for campaigns to logistically pull off a matching campaign.

“It certainly raises eyebrows for anyone who understands the rules governing campaign contribution disclosure requirements and limits,” Krumholz said.

Candidates are not limited in how much money they can donate to their own campaigns, and Krumholz said that campaigns might theoretically be able to match small-dollar donations over a small window of time.

But without a clear explanation, she expects that matching campaigns are really nothing more than marketing tools to generate urgency around supporting a candidate.

“Without a specific explanation of how a match would be accomplished, it seems like a rather disingenuous ploy, using manufactured urgency to raise funds,” Krumholz said.

Max Lee is a recent graduate of Stanford University’s graduate program in journalism. He’s interning for the Colorado News Collaborative through the Stanford Rebele Internship Program. See an explanation of his analysis here.