Editor's note: The Conversation is part of a nonprofit network of newsrooms that taps into academia to write about issues of national concern. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Learn more about The Conversation at https://theconversation.com/us/who-we-are.

By Cutler J Cleveland, Boston University

Alicia Zhang, Boston University

Jacqueline Ashmore, Boston University

and Taylor Dudley, Boston University

Back in in 2018 — in the pre-pandemic world — about 5% of the U.S. workforce teleworked from home. That changed dramatically with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; by May that number had jumped to about 35%. Tech giants Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon and Twitter announced plans to extend teleworking well into the fall and possibly beyond. It’s a sea change that will permanently alter the way America works — and how companies conduct business.

Telework offers a host of potential advantages, including improved productivity, lower costs for employers, greater flexibility and less stress for workers, lower exposure to pollution for commuters and less traffic congestion — not to mention job security during the pandemic for those who can do it. A study conducted in 2017 found that many job applicants valued the option to work remotely and would, on average, accept about 8% lower wages to do so.

Our team is researching connections between the pandemic, how people live and work in cities and city climate action. Transportation is central to this issue because it is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions and access to reliable and affordable transportation is inequitably distributed — and it was severely disrupted by the pandemic.

Early research suggested that teleworking reduced vehicle use — and with it, emissions — so it’s frequently touted as a way to combat climate change. But subsequent studies revealed a more nuanced picture. Our research indicates that a rush to embrace teleworking should be tempered with two realties: Increased telework will exacerbate inequality in America under current economic and social conditions, and the climate benefits are probably very modest, at best.

Skewed opportunities

Opportunities to telework vary greatly in the U.S., depending on race, income level and occupation. About 37% of jobs could be performed entirely at home, particularly in the fields of education and professional, scientific, technical and information services; in management positions; and in finance and insurance.

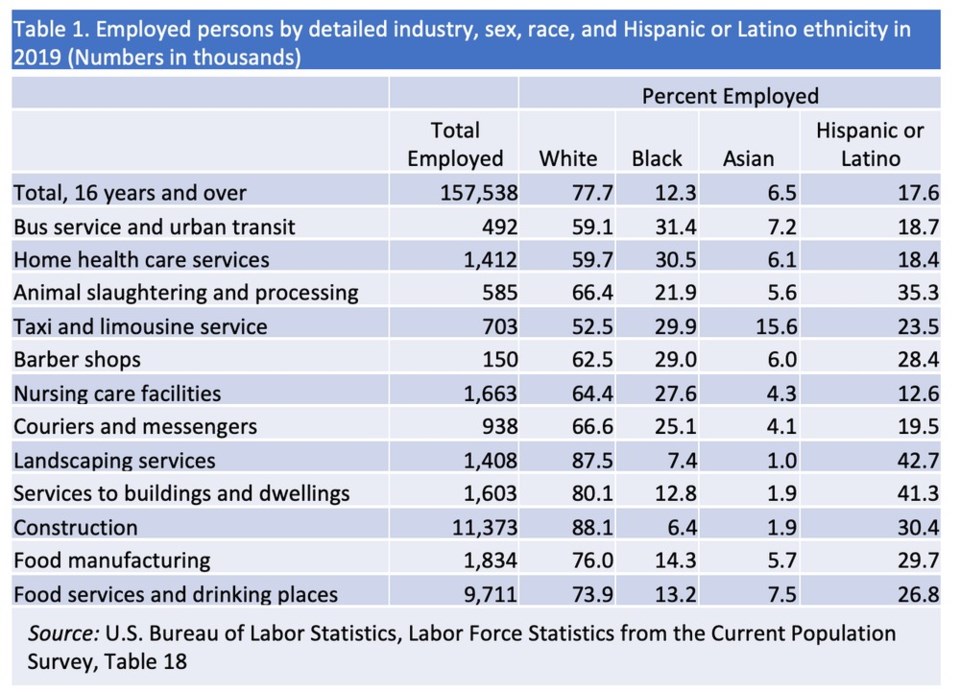

These positions are overwhelmingly held by white Americans. Meanwhile, low-wage, work-from-home jobs are among the few available to people of color. Well-paid telework is a quality of life benefit that is unavailable for many, especially those who are among the bottom half of U.S. wage earners or who lack a college degree. The service sector is a good example, with just 1 in 100 employees able to telecommute. Meanwhile, one-fifth of Black and Hispanic men work in service occupations.

A number of occupations are not suited for telework and are not distributed evenly across the U.S. population.Credit: Cutler Cleveland/Boston University, CC BY

A number of occupations are not suited for telework and are not distributed evenly across the U.S. population.Credit: Cutler Cleveland/Boston University, CC BYPoor teleworking opportunities track alongside disparities in income and education. One in 5 workers in the top 10% income bracket work at home, but for the lowest bracket, numbers drop to just 1 in 100. Education matters, too: 37% of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher reported working from home in 2019 compared with just 16% of those who only held a high school diploma.

Does telework benefit the environment?

So how does teleworking impact the environment? Research has shown that, surprisingly, the climate benefits are lower than conventional wisdom suggests. Overall, it may even increase emissions because of indirect or “rebound” effects. Household energy use rises when people work from home. Prosperity also can increase emissions. Workers save on commuting costs and teleworking boosts labor productivity and wages, allowing increased buying power of goods, services and a greater ability to travel — but each of these have their own associated emissions.

The direct effect of working from home is straightforward: For those who once drove to work, fewer miles traveled translates to fewer emissions. But some telecommuting households actually drive more. Errands once daisy-chained into a morning or evening commute may become multiple trips. In “car-scarce” households, other household members may jump at the chance to use the car. Without having to go into an office every day, there are early signs of people relocating to suburban or rural areas where daily life requires more driving — making for a longer drive when they do have to commute.

Reducing automobile travel is a core strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but our review of the research shows that teleworking is not a panacea in this regard. Other strategies that encourage changes in transportation, such as compact, walkable neighborhoods, more extensive and safe bike lanes and expanded public transit may be better tools to reduce both emissions and inequity.

Urban policies

On its own, further growth in telework will worsen social equity, while offering limited environmental benefits. But cities can address both issues with well-crafted policies. For example, better public transportation reduces emissions and simultaneously benefits people of color who rely on it more than white city residents. Steering energy efficiency programs toward multifamily dwellings that house low-income renters will bring benefits – smaller utility bills, better air quality, improved health and new jobs — to vulnerable households.

We believe the disproportionate number of people of color who cannot work from home deserve targeted assistance in the form of affordable child care, paid sick leave, nutrition assistance and unemployment benefits. And as cities develop climate policies, social equity needs to be a principal objective.

Cutler J Cleveland, Professor of Earth and Environment, Boston University; Alicia Zhang, PhD Student, Earth and Environment, Research Assistant, Institute for Sustainable Energy, Boston University; Jacqueline Ashmore, Executive Director of the Institute for Sustainable EnergyResearch, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Boston University, and Taylor Dudley, MBA Candidate, Questrom School of Business; Research Assistant, Institute for Sustainable Energy, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.